Naturescapes

Featuring works by: Chu Hao Pei, Kumuda, Accidental Artist, Johannes Christopher Gerard

Arranged by: Ong Xiao Yun

Handful of leaves

Buddha in his teachings of the sutta “The Siṃsapā Grove” uses the simile of the leaves covering the forest to illustrate the vast knowledge he has. The fallen leaves he picked up in his hands are the teachings he taught which are beneficial and lead to the path of enlightenment.

In Chu Hao Pei’s artwork, Beneath The Bodhi & Banyan and Three Acts to a Tree, he was addressing the connection and possibilities of (dis)continuity between spiritual practice and the environment. Using the medium of expired films, digital art prints which photographed the tree shrines depicting religious practices and his concerns for the practice in spaces. The artist chose to provide an image of an installation where the images are arranged in a gallery so there is a sense of spaciousness to the art piece and also a feeling of detachment as the images are not clearly in view.

In Three Acts to a Tree, actual leaves were used as materials for his art creations where his actions of collections, observations and investigations on the nature of these leaves introduced the concept of a form of labour for him into his process and thereby an element of time in the production of his artwork. The square-shaped cut leaves embedded in the frame reminds me of gold leaves that devotees used to paste on Buddha statues. And the dissected leaves give an impression of them being specimens which is in line with his process of investigating the nature of the leaves.

Chu Hao Pei

180 x 160cm

Expired film & Digital Fine Art Print on Dibond

2018-2019

https://chu-haopei.tumblr.com/beneaththebodhibanyan

Beneath The Bodhi & Banyan began from my observation of the emergence (and disappearance) of tree shrines over the years. The transient nature of the tree shrines sparked my curiosity in them and led me to trace their origins and their eventual disappearance. As a child I was brought up not to touch or interfere with any religious objects out of respect and taboo. Hence, their removal by the state agencies, justified as an unlawful trespassing on State Land by the authorities1&2, is in tangent with my upbringing and beliefs. Shot in expired film, it draws a connection to the transience nature of the tree shrines.

Their disappearance is especially concerning for me as it suggests that there is perhaps no place for personal spiritual practices of the individual outside of institutional and fixed entities. How does this affect individuals and communities in developing a relationship with place through meaning-making?

Chu Hao Pei

Dissected leaves, leaves ashes and sticker on glass panels

2020

https://chu-haopei.tumblr.com/3actstoatree

Three Acts to a Tree is an adaptation piece conceived in A. Farm Residency. Forced to shelve the initial project plan for the residency, I began exploring the labour through collecting the fallen leaves from the tree in the courtyard of the residency space. Dissecting selected fallen leaves, I directed my attention to the compositions and colours in each frame. In the laborious process, the different compositions of the fallen leaves enunciate the different phases of time. Every frame suggests a different part of time that continues to fade. In this gesture, I visualise my labour through the remnants of the natural world. The collected leaves were burnt and reintroduce back into the space they once reside. The final act (burning) completes the work and my time in the space, paralleling my indifferent time in the residency.

The Lotus Flower

In verse 285 of the Dhammapada, The Story of a Venerable who had been a Goldsmith[1] describes the lotus flower as a meditation object (the white kasina[2]) prescribed by the Buddha to a monk who was the son of a goldsmith. The monk meditating on the arising and passing away of the lotus Flower with its beauty and demise, realises impermanence (aniccā) and was able to gain insight into the three characteristics of existence and eventually attain enlightenment. There is another story of direct experience where the great disciple of the Buddha, Mahakassapa was smiling after seeing Buddha with the golden lotus flower at Vultures Peak.

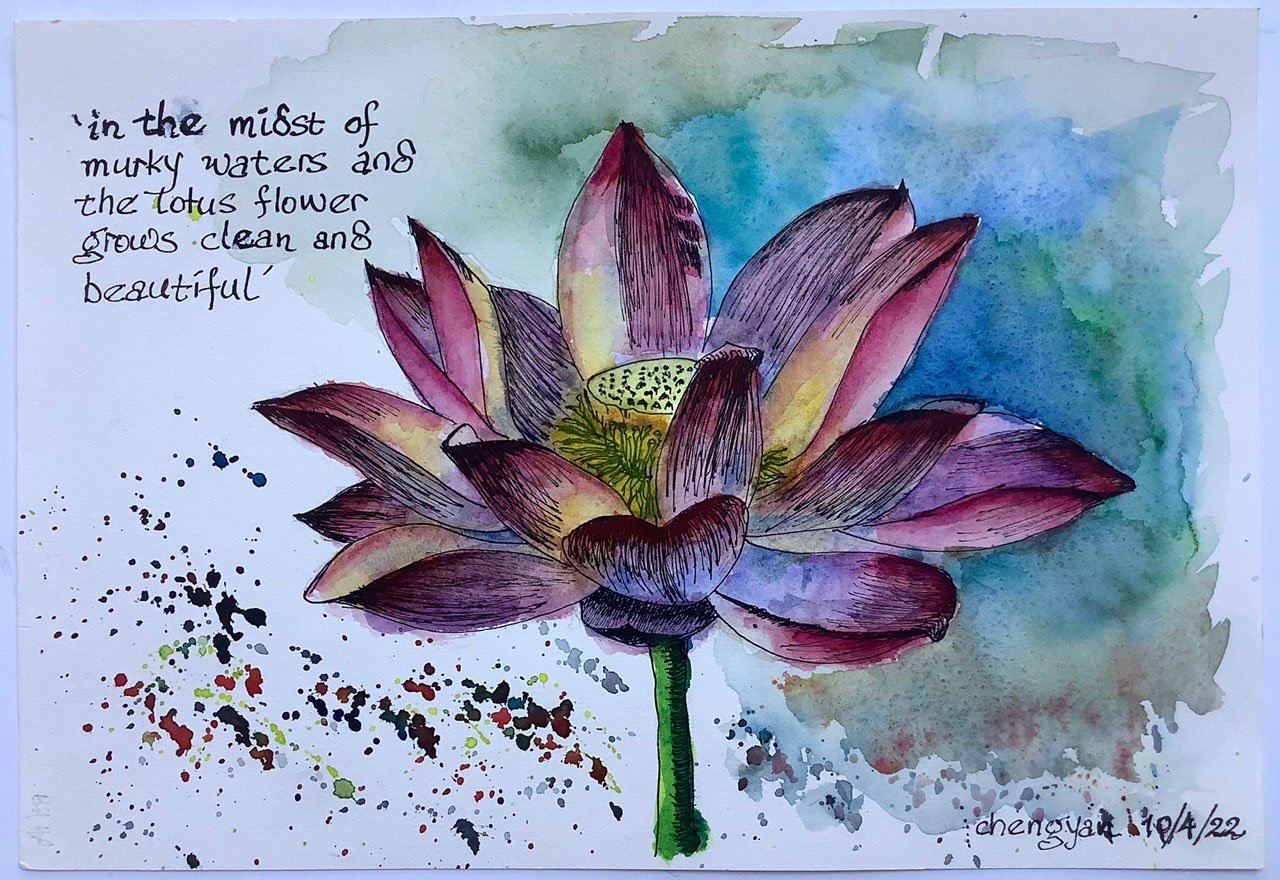

In the symbolic lotus art works by Accidental Artist, Johannes Christopher Gerard and Kumuda, we see the beauty of the lotus flower. Accidental Artist described the lotus flower as elegant with his watercolour painting and handwritten text. The watercolour texture enhanced the natural qualities of the lotus flower which grows in mud, a softness and fluidity of the soil. A retiree now, he paints watercolour to heal and recreate himself.

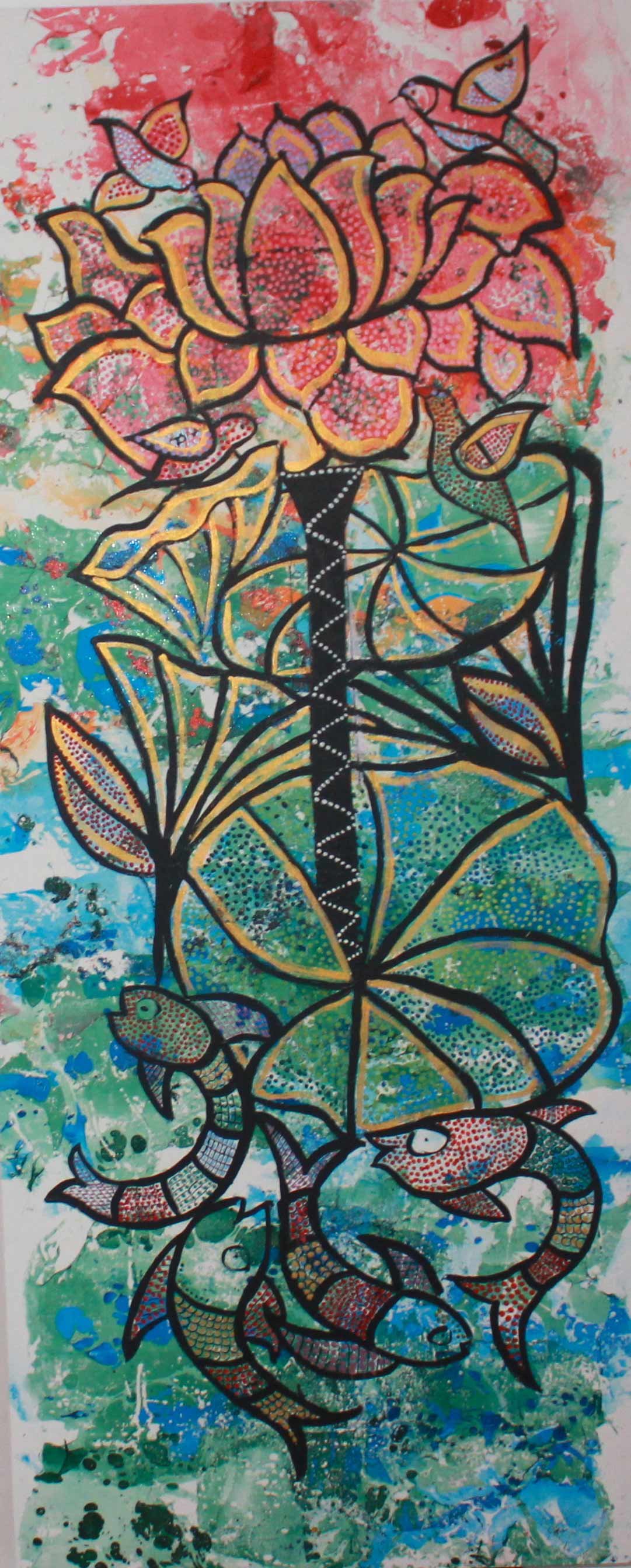

Johannes used photography to capture the blooming lotus flower as a metaphorical representation of enlightenment. We can see individual petals and the overall texture gives a painterly feeling. Kumuda’s lotus painting is abstract with bold black outlines. As the artist describes her artwork, the fishes and birds dance with joy as the lotus reaches up towards the sun. Her technique also incorporates the marbling effect. This makes the colours seamlessly bleed into each other. The dotted pattern gives a meditative quality to the painting.

Accidental Artist "The Elegance of The Lotus Flower" 279mm X 210mm Watercolour 2020 chengyan_c@ yahoo.com.sg

Kumuda ""Rise above the Ordinary is contemporary artwork created to interpret a Buddhist saying which describes the lotus as a flower that rises above the mud to reach for the Sun. a lotus symbolises the meaning of 'dhamma', which can be interpreted as doing your duty to the greatest of your potential. As a lotus flower is born in water, grows in water and rises out of water to stand above it unsoiled, so I, born in the world, raised in the world having overcome the world, live unsoiled by the world. – Gautama Buddha this painting has a background that is created with a marbling effect, called the 'ebru' effect and consists of three colours- blue, green and pink. The bold black lines bring out a powerful image of bold lines depicting the mastery of the artists brushwork. the image has fishes in the water that dance joyfully encouraging the lotus to go upward. the birds in the sky sing and praise the efforts of the lotus." 40 inches X 60 inches Acrylic & Marbling Painting on Canvas 2021 studiokumuda@gmail.com

Johannes Christopher Gerard "A metaphoric symbol of enlightment" 50x50 cm Photography 2021 https://www.johannesgerard.com/english/printmaking/

Consulting References:

1. The Suttanipata, An ancient collection of the Buddha’s Discourses together with its commentaries, Translated from the Pali by Bhikkhu Bodhi

2. Buddhist Art and Architecture, Robert E. Fisher

3. Visuddhimagga, the path of purification, The classic manual of Buddhist doctrine and meditation by Buddhaghosa, Translated from the Pali by Bhikkhu Nanamoli

4. Nature and the Environment in Early Buddhism, S.Dhammika

5. Similies of the Buddha, an introduction, Hellmuth Hecker

6. Samyutta Nikaya, The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Samyutta Nikaya, Translated from the Pali by Bhikkhu Bodhi, Chapter 12, 56 Saccasaṃyutta