Circles

Featuring works by: Carlos Lorenzana, Euginia Tan, Ghaku Okazaki, Hélène Lindqvist, Jacq wang, Jai Ray, Johannes Christopher Gerard, Kath Fries, Kristina Mah, Lucy Mcloughlin, Lynx Ng, Michael Cu Fua, M.S.Turberfield, Hui Yun

Arranged by: Lee Ju-Lyn

Is the circle our favourite shape? This was one of the more immediate ideas after my initial survey of the submissions, wherein the prominence of the shape stood out to me, and I was curious how it might work as an entry point to approach the works. This article details some of my observations and interpretations of the submissions that feature circles noticeably.

I have arranged them according to other obvious points of comparison with one another, such as mediums or subject matter or to draw a contrast between the works, but I was pleasantly surprised to uncover elaborate conceptual similarities between the works. While many of these works readily relate to abstract concepts like interconnectedness and harmony, these works show that the circle can have much other common symbolism and meaning. These range from the sense of fullness to void, light to dark, sounds, the planets and cosmos, eyes and skulls, prayer wheels, mala beads, love and loss… The similarities and differences between these works are mutually illuminating and enriching to the context for interpretations. This reminds me of an analogy for the Buddhist concept of dependent-origination, being of a circle of mirrors surrounding a lamp, with each mirror reflecting not only the light directly from the lamp, but also the lamplight reflected from other mirrors. (Thanissaro Bhikkhu, 2008, The Shape of Suffering: A Study of Dependent Co-arising, Accessed on 5 May 2022 on https://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/thanissaro/shapeofsuffering.pdf, p 5.)

That these works were created and submitted by people from various parts of the world, from cultural backgrounds, working in diverse mediums, further adds to the sense of interconnectedness and inter-being that are central to the symbolism of the circle in Buddhism, regardless of our various traditions. I have thus included some details about the artist’s cultural and religious backgrounds, as well as their approach to artmaking, to be considered alongside the artworks.

Not all the submissions that featured circles were included in this article, for reasons such as their inclusions in other articles, and I hope the readers would also consider the connections between works in this list and others, even those beyond BAM journal, to the circles in your everyday lives and practice.

(This article is recommended for viewing on a desktop. Please hover your mouse over images to view details of the work, or click to enlarge.)

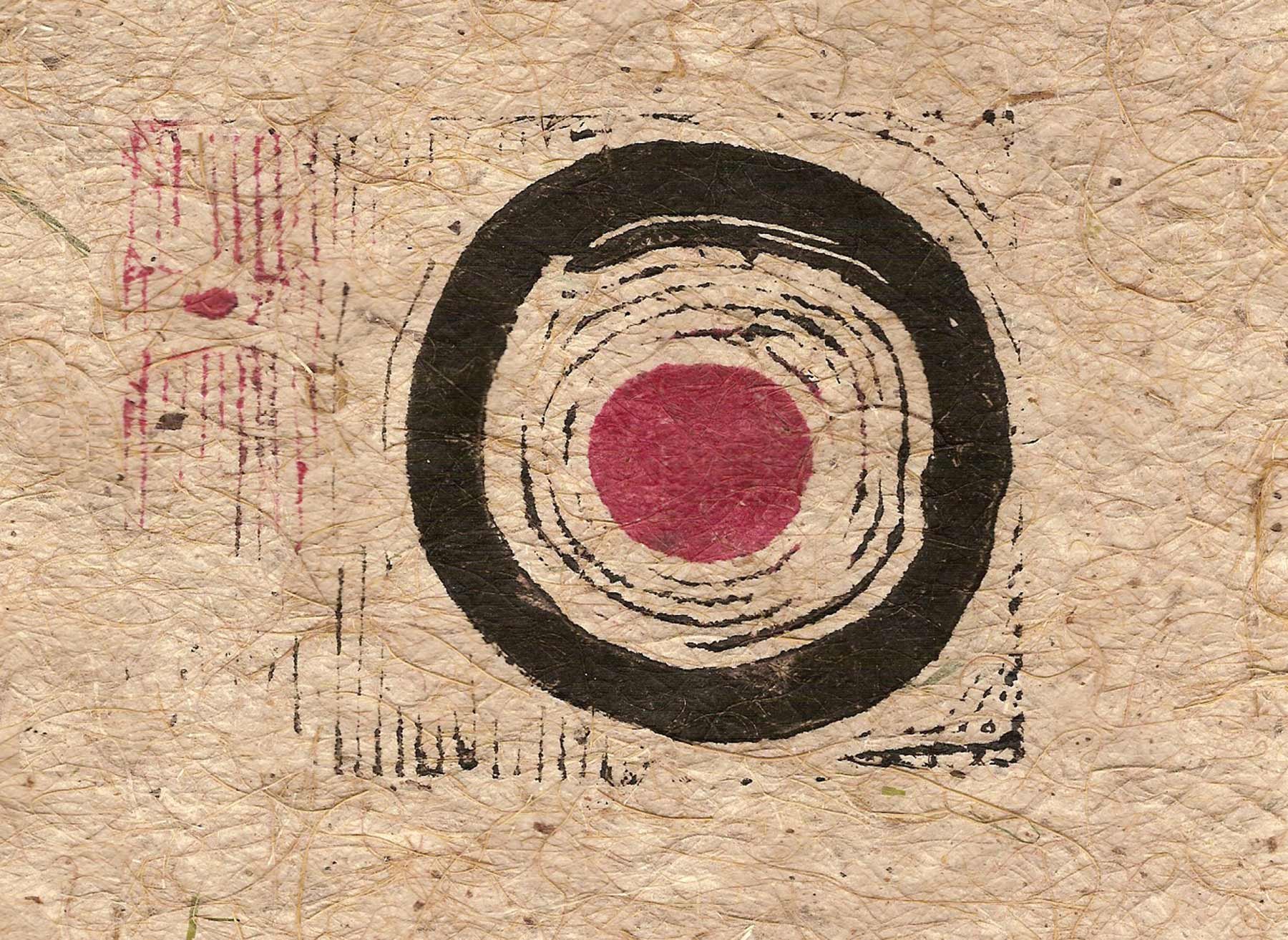

The Clarity and Mindfulness series by Michael Cu Fua (b. 1970, Philippines, Singapore) draws from the “Ensō”. Ensō is a Zen practice of drawing a circle using a single brushstroke as a meditative practice in letting go of the mind and allowing the body to create. In this tradition, the circle can have multiple meanings, such as absolute enlightenment, strength, elegance, the universe, perfection or imperfection. At the same time it may simply be a minimalist expression of ink. A well-known practitioner is the late Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thích Nhát Hanh, whose book, "Fragrant Palm Leaves - Journals 1962 - 1966", inspired Michael for this series. Although he does not consider himself Buddhist, for Michael, the circle also symbolises the circle of life, connection, and one-mindedness. It is a manifestation of the artist at the moment of creation and the acceptance of their innermost self, letting gravity and time take their course.

Hélène Lindqvist’s acrylic painting of a “power circle” was literally the first painting she created as she started full-time painting, for she was previously performing in over 30 leading operatic roles in Germany, Austria, and internationally. She is the child of a Swedish mother and an Egyptian father, she grew up in Stockholm and Los Angeles, and is currently based in Germany. About the work, she shares “In one long session I made myself a power circle. I afterwards gravitated towards painting more figurative art, so this is one of my rare more abstract ones”.

The “incomplete” circle form is also seen in The Miracles of Light in which it is used to convey the glow of lantern lights that is analogous to the dhamma. This work is by Hui Yun (Singapore) who is a Buddhist teaching kids based on the Theravada tradition. She is also open to the Mahayana tradition as is her family. Yunnie, who has a passion for the arts, started drawing when she was a kid and it is something that truly helps her to find peace and cultivate patience. Buddhism helped to shape and form part of her identity.

If circles of light are on one end of the spectrum, then black ones might be on the other. These Linocut prints are from Johannes Christopher Gerard’s Zen and Red Zen series, which is about the bringing of the mind and heart to focus on the essentials. Johannes is based in the Netherlands and a believer of the philosophy of Buddhism; from time to time, he visits the He Hua Temple (Mahayana) in Amsterdam, Netherlands or Fo-Guang-Shan Temple in Berlin, Germany. Born in Germany, and trained in Ireland, Johannes works in the fields of video, performance, photography, installation and printmaking.

In contrast, the circle in Weaving Consciousness by Carlos Lorenzana (Chicago, United States) is more subtle as suggested by the negative spaces between the repetitions. While he does not consider himself a Buddhist, this art piece explores a theme relating to a Buddhist principle that "form is void"- meaning that forms are inseparable from their content. The form of shapes and figures Lorenzana takes on in his paintings are also the forms of their background, an instance of how the correlation between what unifies form and all surroundings are revealed in minute detail. The work is also about interdependence amongst all surrounding and detaching from what is known and weaving positivity to evolve to higher consciousness.

The overlapping and fragmented circles in All Life is Noise by Lynx Ng (Singapore) reflect how amidst the cacophony, a soothing pattern exists for those who are attuned to the frequency. The circles are seemingly broken up and seemingly discordant, yet harmonised by the repetition and palette. Lynx, who does not consider himself Buddhist, hopes that in his endless search for the meaning of life in art, he can edge you a little close to yours.

On the other hand, Goodbye by Jacq Wang (Singapore) presents more disconcerted and almost violent fragments, stemming and disrupting a circle depicted in the lower left of the image. This acrylic painting depicted the circumstances surrounding the sudden departure of her father; how time and love helped to facilitate letting go of intense grief with hopes towards reincarnation for a better life.

While she describes herself as “an amateur artist who paints her dreams and fantasies”, her Let Me Go ironically depicts the irony of being trapped in a bubble and held hostage by our desires to hold on to sufferings, and the accompanying sense of helplessness and isolation. Here, there is clear relevance to the Buddhist ideas on suffering, and its relationship with craving and clinging.

There is not only visual similarity in the compositions of Let Me Go and the works by Lucy Mcloughlin (Singapore) but conceptual connection as well. This work is a reflection on how “If we close our eyes and reach to our core, our true self, our essence, we will allow ourselves to float in the expansive ocean of the universe. Instead, we mostly choose to stay hidden in our shells made up of all of our conditioning layers imposed by society, while time is slipping through. Going through life missing the secrets of the universe”. The circular motif is most obvious in the depiction of the orbiting planets, but there is also the harmonious repetition of arcs like in Lynx’s All Life is Noise, which seems to bear a similar message although depicting very different content.

Though Lucy did not grow up a Buddhist, she has grown to relate the most to Buddhism spiritually and philosophically. While she considers herself not a Buddhist, she has been self-studying and practising Shamatha and loving-kindness meditation regularly for the past 10 years. She has also done a few retreats in Dzogchen Beara Tibetan Buddhist centre in Ireland where she used to live.

Albeit of a contrasting visual style, circles also depict the planets in Life Before Birth by Ghaku Okazaki (b 1988, Japan, working in Germany). These images are also similar in relating individual figures and the cosmos. In this work, circles also manifest as faces, skulls, heads and various parts of the female body, but most of all, as the pupils of the many eyes, including those connected and framing the entire image.

Life Before Birth is a vision of the energetic connection between diverse people and living beings/ways. It is a suggestion that if we can see the world as colourful as it actually is - without the prejudice - we can feel this purely energetic explosion of existence and diversity. For Ghaku, art is the magical technique that enables the visualisation/materialisation of futuristic visions of the connection between us in which the diversity is not denied or oppressed, but affirmed and celebrated. In Ghaku’s artworks, for example, different skin colours turn into rainbow colours. Ghaku grew up in a Buddhist family rooted in Niigata, Japan and follows Zen and Mikkyô, and respects the Buddha, Master Kûkai and other Zen Masters.

Also on interconnectedness and harmony, the works by Kristina Mah (Australia) explore how to evoke interconnectedness, acceptance, impermanence and harmony. Situated at the intersection of philosophy, science, art and design, her work is motivated by concepts grounded in contemplative wisdom traditions, especially Buddhism. Kristina’s Filipino mother and her Chinese-Burmese father met and lived in Thailand, and the family immigrated to Australia in 1987, where she is based and her work Wish Happiness was presented in 2018.

Wish Happiness is a large-scale interactive art installation that invites visitors to generate and transmit a collective wish for peace and happiness to all beings by turning the wheel of positive energy. A carousel structure is transformed into an illuminated wheel encouraging playful interaction with visitors by inviting them with colour and light to turn the base.

Kristina’s other work, Inner Suchness, is an interactive installation that combines digital projection and augmented reality (AR). The artwork reveals multiple layers articulating self-awareness of movements from the inner world of an unfolding journey of her daily contemplative practice of Tonglen, a Tibetan Buddhist meditation for compassion cultivation. Inner Suchness also refers to the metaphor of mandala offerings.

Also conveying Buddhist concepts with installations, sounds, and performance art is Jai Ray (Singapore).

His works from the ANAHATA Series (2017-2020) includes a sound Installation component featuring a round pan that contains oil and water made to vibrate to the artist’s voice. Anāhata (Sanskrit: अनाहत, IAST: Anāhata), which in English means "unstruck", refers to the Vedic concept of Anāhata Nada or 'unstruck sound”, and the series are explorations into the essential nature of Self in Buddhist AbhiDhamma.

Nutcracker (Anattā) is a performance work that explores and enacts (futile and not so futile, skillful and unskillful) ways of approaching the experience of (non-)Self, including trance-inducing movement and sound, and even through the means of ritualised violence. Anattā (Pali: अनत्ता) or Anātman (Sanskrit: अनात्मन्) is the Buddhist doctrine of "non-self" – that no unchanging, permanent self or essence can be found in any phenomenon. The title comes from the idea that “The Self's a tough nut to crack…”

Jai is a Buddhist “currently practising Vajrayana with a foundation in Sutrayana”.

COINS by Euginia Tan

past the freeway

state land mowed grass

past the chants for

an afterlife less crass

third floor, row twenty one.monolithic pillars entomb

all that was never said (or done)

my father blasts a monk’s mantra

from itunes insteadi clean your marbled face

with a wet cloth

flip two newly minted coins

in hopes that you are full.

are you?

have you ate your fill yet?

will you ever?

The idea of ritual is echoed in Euginia Tan’s poem Coins (2016) which describes a person's trip to a Buddhist columbarium and a corresponding divination ritual involving the use of coins. Euginia is not a Buddhist and is “still in the process of discovering” her faith and is based in Singapore.

SANDALWOOD AND BURGUNDY by M.S.Turberfield

When I was a child my father made me a sandalwood mala

With a tassel the colour of deep blood burgundy.And embellished on it a single skull bead

The physical representation of death,

My father had said-

It reminds us that we all die one day.And before you use your mala

hold it in your hands- in your palms

in the crooks of your fingertips

and blow onto the beads,

My father had said

And imagine them turning into dust…

It reminds us that everything will disintegrate one day.And as I pressed my small nose into the beads in my palm

Inhaling the scent that never lingered for more than a moment

I asked “Daddy, why do you have to leave tomorrow?”

Because everyone must leave one day.But don’t worry, it's only for work, he’ll be back by Friday

And as I grew older,

Next Friday turned into next week

And next week turned into

Next month

And I became so accustomed to not seeing him-

(holding my mala in the clasps of my knuckles,

Each bead whispered prayers of his safety

Every time he boarded an airplane)

He became like a ghost.

No more than a memory half the time

When looking into picture frames,

Or holding my mala in the claps of my knuckles

Wearing the beads thin with whispered prayers

Looser and looser

As his scent slowly became that of sandalwood and

The residue of citrus on my fingertips…I worry he will not come home one day.

And on that day, the beads of my mala

Will unravel

And clatter on the wooden floorboards

Like rain.And on that fateful day

I will slowly collect the beads again

(this time he is not there to fix them)

remembering what he had said those many years ago:

that everything must come to an end

One day.When I was a child my father made me a sandalwood mala

With a tassel the colour of deep blood burgundy.

The poem, Sandalwood and Burgundy, is about the connection between her and her father and their faith, as connected and symbolised by the round mala prayer beads. “Sandalwood and Burgundy” revolves around the ideas of inevitable loss, impermanence and absence. She explains, “I wrote this when I was sixteen, having grown up with my father always traveling for work, and yet also being the main connection I had to my faith as a child. Consequently, my relationship with my father & my relationship with my faith is intrinsically linked, and if not, one and the same. This is something that might change with time, however was indeed the case at the point when this poem was written.”

M.S. Turberfield is a Eurasian performer / creative (mixed half British and half Singaporean Chinese) based in Singapore. She grew up as a Tibetan Buddhist, in the Mahayana tradition.

The reference to sandalwood as a material and the theme of connection with one’s father, cues the work of Kath Fries’ (Australia) whose Hold Dear is also a reflection on loss and her father, and features a bronze-cast magnolia branch, coincidentally, resting on a clear round support.

Kath is a Buddhist mainly inclined towards the Zen, Ch'an, Mahayana, and Theravada traditions. Her art practice is an integral part of her Buddhist practice. Drawing from walking meditation and Zen dry-landscape gardens, the circles in “Island within” map her mindful journeys and visualisations of the pressure of each footstep on the ground and the vast fungal mycelium networks beneath her feet. Kath also refers to the late Thích Nhát Hanh, who explains that in walking meditation “each step can bring you back to the island within – back to the wonderful present moment, back to the now.”

Thus, this connects us back full circle to the reference to the late Thích Nhát Hanh in Michael’s Clarity and Mindfulness series, which are the first of the works featured in this article.